Posts filed under ‘Teaching’

Teaching “Active Learning”?

The students left ten days ago. Out the window of the dining car on the Iç Anadolu Mavi Tren, I can see the same Taurus mountains in which we spent time together. I’m returning to Istanbul from Syria. Since the students left, I’ve been thinking again and again about the summer course, about the students, about the whole project of “active learning.”

I was often confused during the seven week seminar. What is “active teaching?” Isn’t all teaching active? And if you are successful in evoking students’ own learning, is there a role for a teacher at all?

I had thought carefully about how to introduce them to Istanbul. I had considered what kinds of ground rules I would to encourage them to make for their dealings with each other. I had hoped to make them comfortable and familiar with the core of Istanbul, so much that they would feel welcome to explore it on their own. And I had assigned a “cultural events” analysis that would require them to leave their apartment and venture into unfamiliar sorts of events.

Did it work? Or should I not have worried about it to begin with? These students were truly remarkable. I came to admire each of them individually, and to marvel at all of them as a collective. They didn’t rest. They worked in the day and engaged with the streets, the cafes, (the bars) at night. There was so much to experience, so little time, they explained. If one is working for “active learning,” and the students learn an enormous amount on their own, is that successful teaching?

The Burch seminars have an innovative design. Faculty and students are expected to explore a topic together. But the university’s expectations for even such an innovative program are rather traditional. I had planned to gather inside a classroom a few hours a day to talk about the readings and our experiences. But there were too many things to experience. The discussion time kept receding into the background as the students kept forging ahead. I kept seeing that they wanted to do many things, but seemed to resist setting aside time to talk about their experiences. Weren’t we supposed to meet and have formal “classes”? We had one difficult discussion on the road to talk about how to schedule both experiences and classes. But it never seemed to work. There were always too many things to see, to do, to learn. In the end, I had to agree. We began to grab whatever time we could. We talked about nationalism, identity, resources, and tourism sitting on the rocks in a beautiful mountain stream. We identified Byzantine iconic representations standing in a cave staring at the paintings. We talked about confusions and reflections over breakfast in a hotel restaurant.

I found that the students had actually been reflecting on all of their experiences–I just hadn’t been around to hear it. They talked in the evenings and at night, listing the things they didn’t understand, the things they really appreciated whether they understood them or not, and the things they had just figured out. (See a list on Emily’s blog.) They posted great photographs and analyzed their days in the blogs they struggled to keep up with. But there was a continuing problem–there would be time to reflect later, but they could only experience NOW!

Sometimes I thought I actually had no role. I set up the course, assigned the reading, planned the introductions, and they did the rest. I still think they were the ones who made the program work. But I hope that my questions–probably much more than my answers to their continuous questions–helped them along the way.

My own reflections from the summer are now focused on the fall. Whatever I did to encourage active learning–should I call it “active teaching”? Is that what keeps students from becoming tourists? Whenever people asked them if they were tourists, they always demurred. No, they answered, we’re students.

From my first visit to Turkey, I was struck by the tourists’ experience. The huge air-conditioned buses that kept them high above the level of the streets took them to the most important monuments and then back again to their western-style hotels. They didn’t ever get to encounter the stuff at street level, have to figure out how to use a squat toilet, taste the local foods, ride the local ferries, see the local poor. They didn’t know about the fascinating and complicated politics, the way children greet their grandparents, or the amazing scenes down by the docks. Tourists live a sanitized existence, free of everything messy but also free of everything fascinating.

Tourists simply sample, never quite engaging local societies, cultures, people. They see the monuments, eat in tourist restaurants, buy the curiosities. I wonder now if that is what the students in my large lecture courses are: tourists. They collect facts, souvenirs of a class that collectively represent the few things they will remember. But they don’t encounter the messy and the fascinating in history, the various ideas that do not connect with each other, the facts that don’t fit together, the big disagreements, the novel ideas and the strange experiences. Like tourists, they expect to be kept from having to grapple with discomfort.

These students were different. They weren’t content to see Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque, go to the covered bazaar, eat Turkish food at tourist restaurants and consume “Turkish culture” at special dedicated evening programs. They wanted to interrogate and explore, to laugh with new Turkish friends and celebrate Turkey’s football victories, to figure out how to use squat toilets and which kinds of foods people really liked. They wanted to travel, to experience–to figure it out for themselves. They know a huge amount now about Turkey, they can get around, they know (for the most part) how not to give offense. They have at least a basic knowledge of Turkey’s history, culture, and language. But I didn’t give it to them. They got it.

We’re not tourists, they insisted to any Turks who asked. We’re students. And I think I get it now–they are students, and I need to work harder to make sure the rest of my students stop being tourists.

Farewell Dinner

And for these students, I have nothing but admiration and gratitude. I was simply awed by the way they treated each other and me. I have never seen another ten people who cared so deeply about each other, helped each other so consistently, worked together so well, and enjoyed each other so continuously. They were amazing to travel with. They took on things by themselves, did difficult tasks without being asked, and never complained about less-than-ideal situations. I was quite grateful for their responses, especially when things did not work out; as one explained, if things aren’t OK, we laugh about it. If they are, we are happy. I am convinced I could never again find a group willing to move so many mattresses, share so much medicine, sleep in such close quarters, or stay so completely flexible in order to take advantage of whatever came up.

Thanks to them all, to Mr. Burch and to the UNC Honors program. Thanks also to all those who agreed to talk with them about various aspects of Turkish life and history and culture, who helped them find what they sought. Thanks to Katie, for her ideas with the planning, and to Friederike for her continuous assistance. And, of course, thanks to William, for his insights and support and for being the best traveling companion one could ever hope to find.

Back in Istanbul

We took the night train back to Istanbul. Despite the fact that only half of us slept, everyone was ready to smile for the final “after” photo. It seems we all found our way back to our places and crashed. Two weeks on the road is a long time, especially with people as amazing as these students. They seem to thrive on minimal sleep, have a vast desire to encounter everything and engage with everyone, and manage to maintain their sense of humor throughout. I learned a lot from them, about mutual respect and support, about learning and teaching, about humor and good fellowship. They are an amazing team, and always managed to work together and anticipate anything we might need. (I turned around after 11 pm at the Ankara train station to see Edward coming out of the train one more time to collect the luggage not only of our three ill students–he took care of mine, too!)

We set aside a little time the next day to talk, but most of the week is devoted to their projects and interviews. Our big event of the week was a visit to the US Consulate. Many of the students are interested in public policy and diplomacy, and an old friend who used to work in the Foreign Service helped us get an appointment. We had a number of briefers, who answered our questions clearly and, I think, honestly.

The condition, though, seemed quite odd, considering our recent experiences. This was an “off the record” briefing. That means, apparently, that we cannot relate what we learned or quote anyone. This is a difficult condition for a historian, though it seems quite common and acceptable for journalists. The briefers simply assumed we understood and would accept the condition, and never sought any kind of agreement from us.

Istanbul’s mufti had seemed surprised at our meeting some weeks ago when he was asked if it would be alright to quote his remarks. Of course, he responded. He seemed confused. If he said something, why wouldn’t he agree to having it quoted? The students have received the same response during interviews. If something wasn’t to be quoted, why would the interviewee say it?

I found the condition particularly strange toward the end of the briefing. US officials emphasized again and again American freedom of speech. Yet here we were, unable to quote their words. In Turkey there are many restrictions to the freedom of speech, but people stand by their words.

The next night, the students threw a terrific Fourth of July party on the terrace. I’m going to miss the view, too.

Ankara

The bus to Ankara turned out to be a bit more exciting than we had planned. The driver claimed he didn’t know he had to stop in Ankara on his way to Istanbul, so insisted on passing the exits. After a series of phone calls, and some remarkably polite and persistent intervention from Yekta, we arrived somewhere–anywhere–in Ankara and got off the bus. We managed to find four taxis despite the late hour (1:30 am) and made our way to the dorms at Bilkent University.

When our planned speaker postponed the next morning, I offered the students a day off to explore Ankara. Instead, they wanted to go out to Gordion, a site where UNC Classics Professor Ken Sams leads an excavation. After taxi, dolmus, and bus rides, we found ourselves looking up at a mound that had previously been a city.

I loved Ken Sams’ discussion. We had encountered many guides who provided details about the stones. Ken is a historian. He told us what is known about the people who had lived at Gordion, how we know the things we know about them, and what we don’t know yet. As we stood looking into the stone walls between structures, he told us that the same things had been found in each. These implements provided information on food and textile manufacturing technology, but not why the same things had been found in each room. Archaeologist still don’t know who did the production, and how labor was organized.

I loved Ken Sams’ discussion. We had encountered many guides who provided details about the stones. Ken is a historian. He told us what is known about the people who had lived at Gordion, how we know the things we know about them, and what we don’t know yet. As we stood looking into the stone walls between structures, he told us that the same things had been found in each. These implements provided information on food and textile manufacturing technology, but not why the same things had been found in each room. Archaeologist still don’t know who did the production, and how labor was organized.

Ken explain to us the kinds of things archaeologists can know, what they wish they knew, why they think other kinds of records may no longer exist. And we learned that archaeologists sometimes revise their previous judgements. We visited the tomb of King Midas. Ken explained, though, that new dating suggested that the corpse was Midas’ father, making it still the tomb that Midas built, but not quite, well, the tomb in which he was buried.

Ken explain to us the kinds of things archaeologists can know, what they wish they knew, why they think other kinds of records may no longer exist. And we learned that archaeologists sometimes revise their previous judgements. We visited the tomb of King Midas. Ken explained, though, that new dating suggested that the corpse was Midas’ father, making it still the tomb that Midas built, but not quite, well, the tomb in which he was buried.

- Into the Tomb

At the small museum next to the excavation, one of the graduate students working at the site explained that the local population had emulated Hellenistic pottery–it was quite the style in some circles. But they didn’t understand some of the Greek pottery’s particular functions, so their imitations are of great interest when analyzing cultural transmission. Ken had talked about the Greeks’ bringing their own languages and customs to Gordion–and to Anatolia generally–but both he and his student emphasized that the local, pre-Greek population remained present throughout the countryside. So what is a “Turk?” It was Phrygians who lived at Gordion–or anyway, it was a Phrygian government who ruled the people. And, it seems, the local population learned from the Greeks, but the Greeks also picked up some of the local customs.

The second Ankara morning was devoted to Atatürk, of course. I got to stay at the dorms with an ill student while William took the students to Anıtkabir, Atatürk’s mausoleum and museum. Their guide was a friend’s father, a retired politician, former cultural minister, and a great admirer of the Founder. After reading of, talking about, and observing the Atatürk cult from afar, the students were able to get right to its center. I am sorry I missed it, but was delighted to hear about what the experience was like for them. (Check out their blogs, links on the right.)

By afternoon, everyone seemed well enough to go to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, where Thomas Zimmermann, archaeologist from Bilkent, talked to us about Turkey’s pre-history. He began outside, talking about the buildings themselves, how the project of taking Ottoman hans and turning them into an archaeological museum was an inherently political project. The goal was to claim a distinctly Turkish past, a past that predated the Ottomans, the Seljuks, and even the Byzantines. It reminded me of the new Lebanese state’s efforts to find its Phoenician past, and the nationalist Egyptians’ attempts to claim Pharonic origin. In this case, the new Turkish nationalists used archaeology to trace a very long historical trajectory, claiming that they descended from the Hattas and the Hittites.

This is an award-winning museum, displayed well and labeled clearly, organized coherently and quite beautifully presented. It creates a linear historical path from pre-historical people to the Turkish present, almost ignoring the Greeks and Romans, who seem to be off limits– invaders instead of true inhabitants of the heartland. I found myself wondering how historians get to choose which groups are authentic and which are outsiders. But in any case, I think the students understand that there is much at stake in the project, more important than memorizing which artifacts go in which era.

Thomas’ fascination with metals was clear–it’s always exciting to have a teacher who is enthusiastic about his work.

A Four Mosque, Two Museum Day

We met the Fez bus for the ride to Konya. Their staff and the driver agreed to a short stop at the Seljuk mosque in Beyşehir on the way. I got to take the microphone and explain to the students–and the others–why the mosque was important. Eşrefoglu mosque is one of the oldest standing wooden mosques, built around 1229. It also functioned as an observatory, the water in the central courtyard was open to the sky, allowing people to watch the movement of the stars and the moon. Astronomy was important for medieval Muslims, initially to indicate days and times of prayer, but eventually simply as scientific exploration. The mosque’s wooden columns and capitals are beautiful, and the tile is that Seljuk blue so different from the blue of the Blue Mosque and other Ottoman monuments.

We arrived in Konya, called our friend Mehmet (owner of a carpet shop, Ipek Yolu), and he brought his pick-up truck to carry our luggage while the students walked to his shop. After we checked in to the hotel around the corner and had lunch, Mehmet drove us around Konya. He not only sells carpets, but has also worked to reintroduce natural dyes to the local producers. First stop was to the home of one of his weavers, a very experienced woman who has been making kilims for him for decades. Pay is $80/square meter, which provides a significant supplement to the family’s income. We saw her weaving a Navajo kilim–another of Mehmet’s new projects. As those of us who have traveled in the American southwest can attest, Navajo blankets and rugs have gotten quite expensive. Mehmet’s weavers are now producing traditional southwestern patterns for sale in Santa Fe.

Next stop was his own dying shop, where he explained the process by which he has tried to match the colors of antique carpets using plant material. The vats are in a large garage, the dyed wool skeins hanging out to dry in the yard. He showed us a terrific old carpet that desperately needs restoring. He unweaves very old undyed kilims to match the old wool, then dyes them to match the color of the antique carpet. An experienced rug knotter will take his wool and restore the antique.

The students were fascinated with the details of weaving, dying and restoring, but some appreciated even more the drive around Konya’s residential neighborhoods. They noticed that very poor households were located in the same neighborhoods as more affluent families, and they enjoyed chatting with the children and petting the cats.

Our second day was the mosque/museum day. Mehmet’s younger brother Muammer was our guide, as we began a day of the kind of intensive high-cultural tourism we hadn’t done since we left Istanbul. I found myself wondering again what the goal of this kind of day is. Is it just exposure to new kinds of things? Some kind of mosque-appreciation project? Museums can be either hours of discovery or bored slow-paced strolling from cabinet to display to statue.

First, it was a 17th century mosque, like a classical Sinan-style mosque updated to baroque. They made the comparisons, got the differences. Then we went to the tomb and attached mosque of Şemsi Tebrizi. There is some dispute about whether Rumi’s teacher is really buried here, and the circumstances surrounding his death. What is certain, though, is that many people see this as a very holy space. The students were impressed with the intensity of feeling displayed by at least one of the visitors–an intensity that Muammer insisted would not have been approved by Rumi himself.

Our third mosque of the day was the central mosque of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, Alaeddin mosque. It is an odd structure, expanded over time as more and more people had to fit inside. The blue-tiled mihrab is striking, as is the intricately carved minber. Most striking is probably the forest of columns and the apparent lack of planning for the whole structure.

Museum one of the day was full of Seljuk-era wood and stone carving. I knew that Konya was an important city on the old silk road. Nonetheless, I was surprised to see the carvings of lions and elephants, and even more astonished with the Seljuk carving of the Buddha.

How would the Seljuks have know to carve elephants? I tried to take the opportunity to reiterate the importance of this region for international trade. We left the museum and hurried many blocks to the tile museum, but it was closed for lunch, so we decided to do the same.

After lunch was the big event of the day. Mehmet had arranged for a local historian to take us to the Mevlana “museum.” Mevlana is the name by which Turks know the best-selling poet in America, the man we call Rumi. The government of the young Turkish Republic outlawed sufi orders, worried that they might become alternative bases of authority. They have turned Mevlana’s tomb, a site of pilgrimage and devotion, into a museum, but a museum in which half of the people are engrossed in prayer and half file through with little understanding of what the building is about.

William and I had been there before, and were struck once again by the intense religious environment that the government was unable to displace when it turned the site into a museum. The mosque/museum tourism day seemed to rise to a whole new level of ambiguity at Rumi’s tomb–the line between the two genres erased more dramatically than it had been even at Hagia Sophia. The tekke in which new members of the order had studied now contains displays of the ways the young students lived, and the devotional turning ceremony has become folkloric dance. The crowds of visiting Turks were here to make a pilgrimage; the crowds of foreign tourists looked quite silly wearing leapord-spotted wraps to cover their shorts-clad legs. It was an odd combination.

Our guide, the local history teacher, seemed, like everyone else in Konya, to have his own narrative about and relationship to Mevlana (Rumi). He claimed that Şems was not Mevlana’s teacher–apparently, it seemed important to him that Rumi come up with his own ideas without anyone else’s help. Muammer was convinced that Rumi was a rational man who emphasized rational discourse and thought and would have profoundly disapproved of the kind of emotional intensity we had seen in the morning. For the religious, he is a spiritual leader and a lover of God. For the secular, he is a notable reformer. For the outsider, he is the teacher who insisted on including all. The “museum” experience of reading and listening to the significance of each object and the way the building was created seemed to detract from the human experience of just simply noticing the feelings of the place and the way people responded to it.

One more mosque on leaving Mevlana: a 19th century structure with large windows and ornate minarets, a mosque that seemed to emulate Dolmabahçe’s style. Very modern, European. Enough mosques! We had seen an impressive range of dates and styles over the course of the day.

We got cleaned up and went to a “traditional” restaurant serving local foods. We ate sitting on the floor around round trays, having no idea that this was to be good preparation for our next journey, to the village.

(Can’t resist another in the continuing McPhotos series)

Walking the King’s Road

Pamukkale to Eǧirdir was on a public bus, larger and more comfortable that what we had taken so far. It was much more conducive to sleep. I think these students need bus rides to sleep–they seem to be awake all the rest of the time.

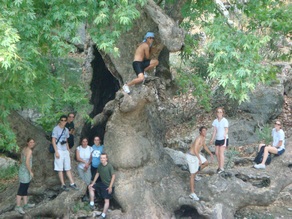

Eǧirdir sits on a large inland lake and is surrounded by spectacular mountains. It is on the way between places, which was our interest in coming. It sits close to the King’s Road that stretched from the Aegean to Persia in the fifth century BC. The Persians used the road for trade, Alexander the Great’s troops marched along it to conquer Darius II, and Paul walked it in his efforts to create converts. We arrived late in the afternoon, talked about Egirdir and history, then the students swam and we all explored the town and its neighboring islands.

The next morning we went to one of Turkey’s national parks to walk part of the ancient road, now called “Yazılı Canyon,” or “with writing.” We looked at the Greek inscriptions on the hillside–and swam in the beautiful mountain river that created the valley. The setting is spectacular, the water is the sort of “mountain stream” that companies bottle and sell. The students seem always to be drawn to high places, and they followed their passion onto the rocks, from which they jumped into the ice cold water.

The next morning we went to one of Turkey’s national parks to walk part of the ancient road, now called “Yazılı Canyon,” or “with writing.” We looked at the Greek inscriptions on the hillside–and swam in the beautiful mountain river that created the valley. The setting is spectacular, the water is the sort of “mountain stream” that companies bottle and sell. The students seem always to be drawn to high places, and they followed their passion onto the rocks, from which they jumped into the ice cold water.

We were delighted to have the park to ourselves, but spent some time on the rocks talking as we dried off. What does it mean that no one was at the national park? Our own national parks are being inundated with tourists, crowded to the point where their resources are compromised. Where do Turks go for vacations? To whom does the Tourism Ministry direct itself? What is the role of tourism in creating a national identity?

As always, the students’ questions and comments were fascinating. Turkey seems to have a two-track tourism effort. For Turks, tourism is about recreation and about education. There is a pass costing only YTL 20 that allows Turks into all major historical and natural sites (unavailable to foreigners who pay admission fees everywhere.) For foreigners, tourism TV ads on European stations emphasize the exotic, the erotic, and the ancient. They left me considering whether, indeed, Turkey’s efforts to present herself as exotic to lure European tourists can possibly be reconciled with her attempts to portray herself as modern and eligible for EU membership.

Ephesus

Our first two days had been grueling, and it had followed some very busy and intense final days preparing for the trip. Every seat on the Fez bus had been full, and none of the 27 seats had been very comfortable. Five hours of battle and battlefield descriptions had delighted only a few of us. The focus on details at the ancient sites had left many confused. The sun was hot, all of us tired, so we offered to let the students sleep late and spend a couple hours at the beach. They hadn’t had any days off in a long time!

We listed the things we could choose from in the area the next day, and asked them to decide what they wanted to see around Selcuk and Ephesus. They produced a schedule that began at 9 am and continued until 10 in the evening. I was impressed!

They were actually ready at 9 in the morning. The first stop: the house where the Pope confirmed that the Virgin Mary spent her last days. This is a small house on a beautiful hillside overlooking Ephesus. We followed a tour group from Italy into the small house. The students’ reactions were varied. Some were clearly touched by the devotion they witnessed, some by their own devotion. Most had never seen anything like the wall to which people were attaching their written prayers.

Then it was down the hill to Ephesus. As a historian, I am painfully aware of my own limitations. I’m always hesitant to repeat “general knowledge,” recognizing how inaccurate it often proves in my own field. So I had welcomed the notion of a tour guide, someone who knew the history of the places we were to visit.

But after three guided tours, I realized the the guides didn’t actually know the history of these places, either. They knew the details of the site. They couldn’t provide context, couldn’t describe the bigger picture, couldn’t explain the importance. I was missing the details, which I had thought were what I really needed to have to talk about these sites. But I realized that the details alone were not enough. And we had alreadt learned to ignore the tour guides. It was time to experiment.

I gave myself a crash course on Ephesus and the way the city grew and changed and moved and adapted to the varied challenges to its population. I did a 15-minute background, then turned the students loose in the most remarkable ancient city I’ve had the good fortune to visit. Clearly, this was not enough. They got the background, but that didn’t help them navigate the city. I walked out of the site again, bought a few copies of an inexpensive book explaining the ruins, and distributed them.

This group is very bright, extremely motivated. With the help of the map and a few of the descriptions, they did a great job showing themselves around Ephesus. They had a broader context, a map to help them figure out where they were, and the details if they wanted them. Nonetheless, I had a sense that I hadn’t provided all they needed. (How much should I provide?) I still have to work on combining teacher and tour guide. Maybe there is something between providing basic background and providing overwhelming detail. I think next time I would send them with a set of questions to find answers to in the ruins.

William orating

William orating

The day continued at their pace. The Ephesus museum followed the site visits, then lunch with a friend of Emily’s family in the beautiful garden of a carpet-weaving school. We talked with one of the owners. They bring girls from the nomadic villagers to teach them to weave (why do they need to be taught in the city?). The course takes 40 days, after which each girl is given a loom and sent home. I asked whether the girls could then sell only to this establishment. No. Why do they? The owner answered that he pays the girls directly, not their fathers or their brothers. That keeps them coming back to sell to him.

I took a “break” (gotta research the next site!) while William and the students went to Pamucak beach nearby. Ephesus used to be at the coast, but persistent silting was one of the reasons for its demise. Now the beach is 7 kilometers away, and provided a wonderful (cooling!) outlet for the students’ boundless energy.

After a very short time back in the pensiyon, we went up the hill to the “Greek” village at the top. We wandered the streets, tasted the various fruit wines, talked with some of the residents, and tried to figure out whether there were any Greeks left, and what Greek might mean in this context.

A Day Off, UNC-student style!

New Stones and Old Stones: Narrating Turkey’s Past

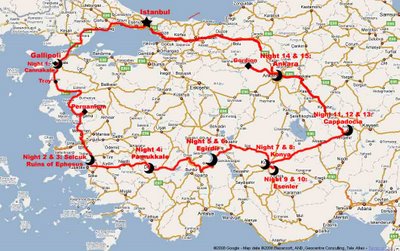

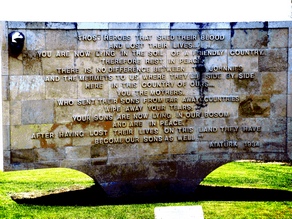

Yesterday it was Gallipoli, today Troy. The tour of Gallipoli took five hours, a very detailed recounting of landings and trenches, battles and bad judgment, famine and disease. The story was told by our Turkish tour guide with a remarkable focus on the British, Australian, and New Zealand forces that had struggled to take the Dardennelles in 1915. The narrative was about their plans, their decisions, their suffering, even their dead. We visited the Allied landing sites, the Allied cemeteries, the Allied memorials, and heard detailed accounts of annual Anzac Day celebrations.

When I found our guide standing alone at the Australian memorial, I couldn’t wait any longer. How do tour guides portray these events and monuments for Turks? I asked. Bülent, our guide (named after one of the chief leftist politicians of the 60s) insisted that he did not do tours for Turkish groups. I asked about what seemed to be a tremendous emphasis on and respect for Turkey’s enemies. He agreed, mentioning Ataturk’s famous quote now prominently displayed at the site. When I mused about whether Turkey might consider the same sort of memorial to Armenians, he deferred. He focuses on Galipoli, and can’t really contribute to the conversation on Armenians.

Bülent told me that there are different sites emphasized in tours for Turks, and over the past few years various municipalities had begun bringing busloads of religious Turks to Gallipoli for free tours.

Indeed, we saw Turks at only three of the 9 sites we visited. We saw them at the trenches, the tour stop that illustrated quite dramatically the proximity of the two groups of combatants: the trenches were very few meters apart. Our penultimate stop, a memorial to the Turkish dead, was quite crowded with Turkish busses (from Zetinburnu, Kacamustafapasa municipalities). Bülent explained that the government was trying to turn Galipoli into a pilgrimage site, a sacred space, because of the number of Turks who had died during the battles there. Indeed, the place has become an open-air mosque, complete with a fountain in the courtyard and a mihrab inside the inner walls.

Turks were also predominant at the highest site, where Mustafa Keml (Atatürk) had seen the Allied landings and urged his troops to great sacrifice in order to stop it. The Turkish tour guide was speaking to his audience in the shadow of an enormous statue of Atatürk.

In my Modern Middle East lectures, I often present Gallipoli as a prequel, Ataturk’s life before he took off his Ottoman uniform and joined the opposition to the Allies and the Sultan in 1918. According to many of the people we have spoken with, and a fascinating article by Esra Ozyurek, the renewed reification of Ataturk is largely a response to the growing power of Islamist politics. Although the five other fundamental principals of Kemalism may be eroding, secularism seems to be keeping center stage. Too bad I missed the photograph of the two high-school girls wearing the “turban” headscarves so offfensive to the Kemalists. They were leaving the area of the trenches using a Turkish flag as a shawl.

As the Fez bus wound its way from Çanakkale to Selçuk the next day, we stopped for tours of much older stones than those memorializing the World War I dead. First stop, Troy. Our tour guide provided a photo opportunity to see the Trojan Horse that Brad Pitt had touched (!), retold the mythology of the Illiad, and walked us through the myriad levels of “Troy.” He was more than a bit confusing, apparently unable to distinguish between myth and history, or even to comment on the extent to which myth had influenced our perceptions of history.

This was antiquarianism of stones, and some of his explanations seemed most unlikely. The high point of the stop was Zoe climbing the walls of Troy (the Turks don’t keep people off many of the ruins).

From Troy, to Bergama (Pergamum), another set of ruins, this one much more convincing. This was the only female tour guide I have seen in Turkey so far. She did a better job, at least explaining how the city had functioned, and where things were located. She paused for reasonable intervals to let us climb around.

The views were awesome–it is located high on a hill–and the students immediately took to posing. They were particularly delighted with the columns, and decided to retake their “senior pictures” leaning on real pillars instead of the photographers’ substitutes in their home towns.

What had all these to do with “Turkish” identity? How do today’s Turks incorporate all these stones into their own collective memory? The only clues we had was a statue defining Homer as an “Anatolian.”

By the time we arrived in Selçuk, I realized that tour guides would not give us what we wanted. Stones are fascinating, but we wanted to know about who had built and lived in them.

Church to Mosque

After last week, I thought we needed to take things a bit slower. Monday had not been a promising start–we grappled with questions of Turkey, religion, and politics from 10 am until dinner was over nearly 11 hours later.

Tuesday we got to enjoy the final student site presentations. The morning was at Kariye museum, a strangely asymmetrical domed structure with the most remarkable and spectacular mosaics still intact. William and I had gone to the old Byzantine church-turned mosque-turned museum some years ago with our kids and our friend Bob Ousterhout, who had written his dissertation on the structure. He is one of the most remarkable teachers I have ever met, and his explanations have stayed with me.

Tuesday we got to enjoy the final student site presentations. The morning was at Kariye museum, a strangely asymmetrical domed structure with the most remarkable and spectacular mosaics still intact. William and I had gone to the old Byzantine church-turned mosque-turned museum some years ago with our kids and our friend Bob Ousterhout, who had written his dissertation on the structure. He is one of the most remarkable teachers I have ever met, and his explanations have stayed with me.

Then it was Kalenderhane, another Byzantine church recreated as a mosque. Both student pairs described the transition, and Zoe actually distributed a page with the basic mosque structures that the students colored while she described the basic needs for the conversion.

All day Wednesday we had conferences to talk about oral history and final projects, and Thursday provided everyone with some work time. Thursday evening was party time! Robin, the wonderful landlord, brought the Efes and some Turkish food, the students provided soft drinks, fruits and vegetables. William grilled, and the Burch students met a group of visiting music students and a number of Robin’s friends. The view, both on and off the terrace, was terrific.

Secularism, Turkish-style

We had to “finish” the history of Turkey this week, before we could really begin our travel around Turkey and the big projects. Feroz Ahmad’s narrative is not quite chronological, so we began Monday morning in a stereotypical, not quite creative, manner: building a collective timeline. But the timeline made Turkey’s political instability quite clear. How does Ahmad account for this instability? Taking the same information he presented, what other explanations might be possible?

We were immediately into a heady argument that seemed to recreate the dialogues among Turks over the past decades. It was the army, with its continuous interventions, that allowed politicians to be irresponsible and unaccountable because they always knew the military would fix the messes. No, no, the army was absolutely essential to the new Turkish Republic to keep it on the right path. It wasn’t the army, a third group argued, but the insistence on applying the principles of Kemalism in circumstances that demanded other approaches, the reification of decades-old goals and the controversies over how to implement them.

We ended the discussion before we had figured it out (of course!) in time to find our way to Suleymaniye, where my colleague Omid Safi had arranged a meeting with Istanbul’s mufti for both of our groups (and a few others). For the Burch students, it was an opportunity to try to understand the confusing relationship between Turkey’s religious and political institutions. They had just read an article by Haldun Gülalp explaining that secularism in the new Turkish Republic required both the privatization of faith (taking religion out of the public–and political–sphere) and, ironically, the control of the state over all religious institutions. The mufti spoke briefly, then answered questions. Some seemed strangely irrelevant, while others began to clear up our confusions. The mufti is employed by the government; he administers institutions that train those who do the call to prayer and the schools that train the jurists and control religious education in public schools.

We had to leave quickly to go to Yildiz University (our third campus tour) to talk with Professor Gulalp. The students asked him their questions about his article, about the relationship between the state and religion, and about his own answer to the morning’s question. Why is Turkey so unstable? He disagreed with all of their opinions, focusing instead on explaining how the military justifies their interventions (Rousseau’s notion of the difference between the popular will and the popular sentiment.) Once again, I was impressed with the students’ insights, and their clarity in both asking and responding to questions. Many carried the discussion into their own blogs (click links on the right).

Experiential Learning

This was the educational philosophy we advocated when I headed UNC’s first year seminar program–that students learn better when through experience and discovery. This week, from Monday’s walking the Byzantine land walls to Friday’s site visit to a hamam, I learned that “experiential learning” really is effective–and, sometimes, a bit awkward.

And exhausting. I’m quite behind in the blog posting because the end of each day has come very late this week, because there is always tomorrow to prepare, because I’m experiencing so much I haven’t time to write about it. The students’ blogs seem a few days behind, too.

Before the week even began, we were scrambling to make the schedule work. Monday’s weather looked like it would be fine and cool, perfect to walk the land walls from the Sea of Marmara to the Golden Horn. David made this map. During the Byzantine period, the entire city was surrounded by walls. Many are crumbling now; some are in the process of being restored.

We began at Yedikule, the seven tower structure the Turkish government turned into a park. The views from the top were spectacular, though, an acrophobe since childhood, I only climbed one tower. The students quickly learned that I was very nervous with their energetic wall-scaling. They delighted in seeing me anxiously cover my eyes, and seemed to become more and more outrageous to get the response. They are all adults, I kept reminding myself.

The walls go through fascinating areas of the city, cutting through sections tourists don’t see. We wondered why so few tourists walked the walls, and how people who lived along these millenium-old structures perceived them. Many of the neighborhoods we walked through were quite run-down, the people very poor. Some of the unused archways seemed to house the homeless. At the same time, the government seems to be investing large sums in restoring sections of the walls. What do the walls mean? How do the Turks view them? What is it like living in a place with so much history?

All back down safely!

All back down safely!

The week seems a blur now. There is so much to see and to do, that we planned things for mornings, afternoons, and evenings. Tuesday we visited an NGO that focuses on women and Islam, and listened to a wise woman answer many questions. I’ve been struck for years that Cemalnur’s answers only seem to make sense some time later. Instead of simple answers about religion and the state, what the NGO does, how sufis are different from other Muslims, she tells stories and suggests parallels. When we returned to Europe, two of the students did the first site project: Sirkeci (the 19th century train station) and the Orient Express it hosted. They spoke of the way the railroad tied Istanbul with western Europe, of the elites that frequented it and the culture they fostered, of the effects of railroads on the Ottoman (and later Turkish) state.

Then most of us went to Tumata to hear Tatar and Uyghur folk music played on remarkable instruments in a musical museum. Like last week, the music gradually became more devotional and the audience more participatory, various students began to figure out how to play the drums that the regulars handed them, and one of the regulars began to turn–the sema.

As we prepared to leave, they insisted we stay for soup, then for dinner, then for the celebration of the birthday of one of the musicians. When I returned upstairs after helping put away dishes, I found all the UNC students up and dancing with the musicians.

Wednesday was museum day, Dolmabahce in the morning, and the Military Museum in the afternoon. Two students took us through the Military Museum, emphasizing how the choices and content of the exhibits reflected the way the Turkish directors wanted their history to be understood. Thursday we visited Bogazici University, where Sevket Pamuk did a remarkable presentation on changes in the Turkish economy over the past century–and hosted us for lunch! The students returned in time for Turkish class. They can put verbs in their sentences now.

Friday morning we sat in the courtyard of the “Blue Mosque” and heard stories about the man who built it, about his life and the issues surrounding his accession to the Ottoman throne, about his goals for the structure and the reason he placed it where he did. Then Gunhan, an Ottoman historian who doubled as a tour guide, took us inside, talked about the tiles and the structures, the arches and the domes. Over lunch, we talked about history writing and national identity, about the challenges of being a historian. Then he took us to neighboring Aya Sofya and did the same thing! We learned about the Emperor who build it, the reasons he needed such a monumental structure, the design and the redesign, the mathematicians who worked out a way to keep such a massive dome from falling. And I learned that it is just as striking to walk into Aya Sofya regardless of how many times one has seen it before. Gunhan was amazing, wearing his tour guide license along with his historian hat. Again I was struck that the “gee whiz” of tourism is a delightful but limited phenomenon. History matters, even (especially?) in the face of spectacular structures.

Two of the students had decided that they would do their site presentation on hamams. After telling us about the origins, economy, and social functions of public baths, we actually did one. Gedikpaşa built his hamam in 1475, making it one of Istanbul’s oldest. It’s a bit rundown at this point, and hasn’t been restored to tourist/spa quality, which is one of the reasons the students wanted us to go there. Countless groups of women have used it over the centuries to wash–and to recreate community. It was amusing to watch that happen, as the UNC women began to splash water around and sing. Needless to say, I’ve no idea how much splashing went on on the men’s side.