Archive for June, 2008

Pamukkale

We were all sad to say goodbye to the guesthouse and Ephesus. We had had a terrific “day off,” and most of the students slept on the bus to try to catch up!

Pamukkale was the next stop. It is named after the white calcium cliffs that rise above the town. Its waters have been considered good for healing for centuries, and many before the Romans had built on top of the cliffs. After years as a major tourist site with a number of five-star hotels at the top, the UN declared the spot a World Heritage Site, insisted on removing the hotels, and revised the water supply so that the calcium-rich water continued to build up and repair the previous decades’ damage.

It is amazing to climb the hillside. It looks glacial, and I expected that, when I took off my shoes (required), my feet would be in icy water. It looks like ice, but feels quite warm. People played in the pools all the way up to the top, where a swimming pool beckons. You can “swim among the ruins,” the pillars and capitals and various ruins in the warm-water mineral-which swimming pool. Needless to say, the students swam.

Before we headed up, I had provided a background to the site and to Hierapolis, the ruined city at the top of the hill. After the swimming pool closed, we walked to the Temple of Apollo and the Plutonium. I’d prepared information about six major buildings at the site, but the third was a theater with a stunning view of the countryside below– and a fantastic sunset. They climbed around the theater until it was dark, looking for the images I had asked them to find and enjoying the remarkable setting.

Needless to say, it was difficult to leave Pamukkale, too. I’ve never encountered a group like this. Each evening since we left Istanbul, they have declared it the best day yet. It’s hard not to be enamoured of that kind of attitude!

Ephesus

Our first two days had been grueling, and it had followed some very busy and intense final days preparing for the trip. Every seat on the Fez bus had been full, and none of the 27 seats had been very comfortable. Five hours of battle and battlefield descriptions had delighted only a few of us. The focus on details at the ancient sites had left many confused. The sun was hot, all of us tired, so we offered to let the students sleep late and spend a couple hours at the beach. They hadn’t had any days off in a long time!

We listed the things we could choose from in the area the next day, and asked them to decide what they wanted to see around Selcuk and Ephesus. They produced a schedule that began at 9 am and continued until 10 in the evening. I was impressed!

They were actually ready at 9 in the morning. The first stop: the house where the Pope confirmed that the Virgin Mary spent her last days. This is a small house on a beautiful hillside overlooking Ephesus. We followed a tour group from Italy into the small house. The students’ reactions were varied. Some were clearly touched by the devotion they witnessed, some by their own devotion. Most had never seen anything like the wall to which people were attaching their written prayers.

Then it was down the hill to Ephesus. As a historian, I am painfully aware of my own limitations. I’m always hesitant to repeat “general knowledge,” recognizing how inaccurate it often proves in my own field. So I had welcomed the notion of a tour guide, someone who knew the history of the places we were to visit.

But after three guided tours, I realized the the guides didn’t actually know the history of these places, either. They knew the details of the site. They couldn’t provide context, couldn’t describe the bigger picture, couldn’t explain the importance. I was missing the details, which I had thought were what I really needed to have to talk about these sites. But I realized that the details alone were not enough. And we had alreadt learned to ignore the tour guides. It was time to experiment.

I gave myself a crash course on Ephesus and the way the city grew and changed and moved and adapted to the varied challenges to its population. I did a 15-minute background, then turned the students loose in the most remarkable ancient city I’ve had the good fortune to visit. Clearly, this was not enough. They got the background, but that didn’t help them navigate the city. I walked out of the site again, bought a few copies of an inexpensive book explaining the ruins, and distributed them.

This group is very bright, extremely motivated. With the help of the map and a few of the descriptions, they did a great job showing themselves around Ephesus. They had a broader context, a map to help them figure out where they were, and the details if they wanted them. Nonetheless, I had a sense that I hadn’t provided all they needed. (How much should I provide?) I still have to work on combining teacher and tour guide. Maybe there is something between providing basic background and providing overwhelming detail. I think next time I would send them with a set of questions to find answers to in the ruins.

William orating

William orating

The day continued at their pace. The Ephesus museum followed the site visits, then lunch with a friend of Emily’s family in the beautiful garden of a carpet-weaving school. We talked with one of the owners. They bring girls from the nomadic villagers to teach them to weave (why do they need to be taught in the city?). The course takes 40 days, after which each girl is given a loom and sent home. I asked whether the girls could then sell only to this establishment. No. Why do they? The owner answered that he pays the girls directly, not their fathers or their brothers. That keeps them coming back to sell to him.

I took a “break” (gotta research the next site!) while William and the students went to Pamucak beach nearby. Ephesus used to be at the coast, but persistent silting was one of the reasons for its demise. Now the beach is 7 kilometers away, and provided a wonderful (cooling!) outlet for the students’ boundless energy.

After a very short time back in the pensiyon, we went up the hill to the “Greek” village at the top. We wandered the streets, tasted the various fruit wines, talked with some of the residents, and tried to figure out whether there were any Greeks left, and what Greek might mean in this context.

A Day Off, UNC-student style!

New Stones and Old Stones: Narrating Turkey’s Past

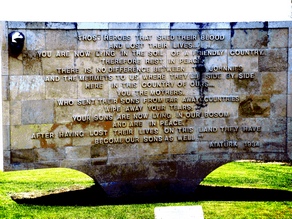

Yesterday it was Gallipoli, today Troy. The tour of Gallipoli took five hours, a very detailed recounting of landings and trenches, battles and bad judgment, famine and disease. The story was told by our Turkish tour guide with a remarkable focus on the British, Australian, and New Zealand forces that had struggled to take the Dardennelles in 1915. The narrative was about their plans, their decisions, their suffering, even their dead. We visited the Allied landing sites, the Allied cemeteries, the Allied memorials, and heard detailed accounts of annual Anzac Day celebrations.

When I found our guide standing alone at the Australian memorial, I couldn’t wait any longer. How do tour guides portray these events and monuments for Turks? I asked. Bülent, our guide (named after one of the chief leftist politicians of the 60s) insisted that he did not do tours for Turkish groups. I asked about what seemed to be a tremendous emphasis on and respect for Turkey’s enemies. He agreed, mentioning Ataturk’s famous quote now prominently displayed at the site. When I mused about whether Turkey might consider the same sort of memorial to Armenians, he deferred. He focuses on Galipoli, and can’t really contribute to the conversation on Armenians.

Bülent told me that there are different sites emphasized in tours for Turks, and over the past few years various municipalities had begun bringing busloads of religious Turks to Gallipoli for free tours.

Indeed, we saw Turks at only three of the 9 sites we visited. We saw them at the trenches, the tour stop that illustrated quite dramatically the proximity of the two groups of combatants: the trenches were very few meters apart. Our penultimate stop, a memorial to the Turkish dead, was quite crowded with Turkish busses (from Zetinburnu, Kacamustafapasa municipalities). Bülent explained that the government was trying to turn Galipoli into a pilgrimage site, a sacred space, because of the number of Turks who had died during the battles there. Indeed, the place has become an open-air mosque, complete with a fountain in the courtyard and a mihrab inside the inner walls.

Turks were also predominant at the highest site, where Mustafa Keml (Atatürk) had seen the Allied landings and urged his troops to great sacrifice in order to stop it. The Turkish tour guide was speaking to his audience in the shadow of an enormous statue of Atatürk.

In my Modern Middle East lectures, I often present Gallipoli as a prequel, Ataturk’s life before he took off his Ottoman uniform and joined the opposition to the Allies and the Sultan in 1918. According to many of the people we have spoken with, and a fascinating article by Esra Ozyurek, the renewed reification of Ataturk is largely a response to the growing power of Islamist politics. Although the five other fundamental principals of Kemalism may be eroding, secularism seems to be keeping center stage. Too bad I missed the photograph of the two high-school girls wearing the “turban” headscarves so offfensive to the Kemalists. They were leaving the area of the trenches using a Turkish flag as a shawl.

As the Fez bus wound its way from Çanakkale to Selçuk the next day, we stopped for tours of much older stones than those memorializing the World War I dead. First stop, Troy. Our tour guide provided a photo opportunity to see the Trojan Horse that Brad Pitt had touched (!), retold the mythology of the Illiad, and walked us through the myriad levels of “Troy.” He was more than a bit confusing, apparently unable to distinguish between myth and history, or even to comment on the extent to which myth had influenced our perceptions of history.

This was antiquarianism of stones, and some of his explanations seemed most unlikely. The high point of the stop was Zoe climbing the walls of Troy (the Turks don’t keep people off many of the ruins).

From Troy, to Bergama (Pergamum), another set of ruins, this one much more convincing. This was the only female tour guide I have seen in Turkey so far. She did a better job, at least explaining how the city had functioned, and where things were located. She paused for reasonable intervals to let us climb around.

The views were awesome–it is located high on a hill–and the students immediately took to posing. They were particularly delighted with the columns, and decided to retake their “senior pictures” leaning on real pillars instead of the photographers’ substitutes in their home towns.

What had all these to do with “Turkish” identity? How do today’s Turks incorporate all these stones into their own collective memory? The only clues we had was a statue defining Homer as an “Anatolian.”

By the time we arrived in Selçuk, I realized that tour guides would not give us what we wanted. Stones are fascinating, but we wanted to know about who had built and lived in them.

To Eyup

I had never gone all the way up the Golden Horn to Eyup, but knew that would be an important part of our explorations of Turkish culture. I thought a stop at the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate on the way, and a walking tour of the old Jewish community area of Balat would be important ways to consider Turkey’s tolerant past. But the day was hot, and the students a bit tired. We had actually hired a guide this time, who took us first to Rustem Paşa mosque, one of my favorites, a small mosque built by the great architect Sinan. It’s hard to find the structure, surrounded as it is by the buildings that have grown up around it.

We decided to take the boat to Fener instead of walking all the way, and when we got to Fener found the Patriarchate closed for cleaning for another hour. We walked up the steep hill to a Greek Orthodox high school, now with dozens instead of hundreds of students.

Back down the hill we visited the Bulgarian Orthodox church, a pre-fabricated structure built in Vienna in the late 19th century and assembled on a site just off the water. After lunch, we returned to view the building housing the Patriarch of Constantinople, a remarkably ornate and guilded structure to which the Patriarch moved in the 17th century. It is a far cry from Aya Sofia, earlier center of Orthodox life before the Ottoman conquest in 1453.

Then we had to decide whether to keep walking (it was getting hotter) or just take the boat to Eyup. Some had had enough monuments (mosques and churches) and wanted to focus on neighborhoods. (Reminded me of a friend’s characterization of the ABC’s of European tourism: Another Bloody Church, Another Bloody Castle.) But Eyup is different.)

We decided to take the ferry all the way to Eyup.

After a gondola ride up the mountain for tea in Pierre Lotti’s café (Freely claims it wasn’t really), we walked to the pilgrimage site. The guidebooks claim Eyup as one of the holiest sites for Muslims, the place where Prophet Muhammad’s standard-bearer Eyup was buried after dying in an unsuccessful effort to take Constantinople in the 7th century. The guide repeated the tour books: an Ottoman religious man dreamed the location of Eyup’s body shortly after the conquest of the city in 1453. As Freely and Sumner-Boyd point out, however, medieval texts describe the site of Eyup’s tomb over the intervening centuries, and the Byzantines had treated the site with respect. Is the guide’s story an effort to pretend that the Byzantines were not tolerant, or is it a way to show that Muslim mystics have powerful dreams? (A few years ago, we were struck by the Budapest population’s respect for the Ottoman conquerors–clear at their military museum–and that they had maintained and beautified the tomb of Gül Baba, a Muslim religious leader during the Ottoman period. It seems tolerance and intolerance have historically gone both ways in the past, but that present elites seem mostly to emphasize each other’s intolerance.)

The tomb of Eyup is clearly not only a venerated site, but a loved space. People’s devotion was clear in the way they walked into the tomb, touched the screens and the windows that protected both the tomb and a stone with the Prophet’s footprint. People exited walking backward, women stroked the stones and kissed the screens. Turkish boys, circumcised as young children, are dressed in distinctive outfits for the day’s celebrations. Many families come to Eyup’s türbe as part of the celebration. Like us, it seemed, many of the Turkish women were wearing headscarves just for their visit to the tomb.

The difference between the tomb at Eyup and Istanbul’s large, touristic mosques was palpable. This is a place of devotion, in addition to aestetic apreciation. People begin praying outside, hands held open, concentrating. The students asked why the place was so significant. It is the closest connection possible with the lifetime of Muhammad. Kevin asked about orthodox Islam’s insistence that there be no intercessor between the person and God–what is this veneration of saints? This is, of course, one of the resons that Salafis (“fundamentalists,” Wahabbis, and others) have, over time, tried to destroy the tombs of important forebears. Great questions, these students have!

Church to Mosque

After last week, I thought we needed to take things a bit slower. Monday had not been a promising start–we grappled with questions of Turkey, religion, and politics from 10 am until dinner was over nearly 11 hours later.

Tuesday we got to enjoy the final student site presentations. The morning was at Kariye museum, a strangely asymmetrical domed structure with the most remarkable and spectacular mosaics still intact. William and I had gone to the old Byzantine church-turned mosque-turned museum some years ago with our kids and our friend Bob Ousterhout, who had written his dissertation on the structure. He is one of the most remarkable teachers I have ever met, and his explanations have stayed with me.

Tuesday we got to enjoy the final student site presentations. The morning was at Kariye museum, a strangely asymmetrical domed structure with the most remarkable and spectacular mosaics still intact. William and I had gone to the old Byzantine church-turned mosque-turned museum some years ago with our kids and our friend Bob Ousterhout, who had written his dissertation on the structure. He is one of the most remarkable teachers I have ever met, and his explanations have stayed with me.

Then it was Kalenderhane, another Byzantine church recreated as a mosque. Both student pairs described the transition, and Zoe actually distributed a page with the basic mosque structures that the students colored while she described the basic needs for the conversion.

All day Wednesday we had conferences to talk about oral history and final projects, and Thursday provided everyone with some work time. Thursday evening was party time! Robin, the wonderful landlord, brought the Efes and some Turkish food, the students provided soft drinks, fruits and vegetables. William grilled, and the Burch students met a group of visiting music students and a number of Robin’s friends. The view, both on and off the terrace, was terrific.

Secularism, Turkish-style

We had to “finish” the history of Turkey this week, before we could really begin our travel around Turkey and the big projects. Feroz Ahmad’s narrative is not quite chronological, so we began Monday morning in a stereotypical, not quite creative, manner: building a collective timeline. But the timeline made Turkey’s political instability quite clear. How does Ahmad account for this instability? Taking the same information he presented, what other explanations might be possible?

We were immediately into a heady argument that seemed to recreate the dialogues among Turks over the past decades. It was the army, with its continuous interventions, that allowed politicians to be irresponsible and unaccountable because they always knew the military would fix the messes. No, no, the army was absolutely essential to the new Turkish Republic to keep it on the right path. It wasn’t the army, a third group argued, but the insistence on applying the principles of Kemalism in circumstances that demanded other approaches, the reification of decades-old goals and the controversies over how to implement them.

We ended the discussion before we had figured it out (of course!) in time to find our way to Suleymaniye, where my colleague Omid Safi had arranged a meeting with Istanbul’s mufti for both of our groups (and a few others). For the Burch students, it was an opportunity to try to understand the confusing relationship between Turkey’s religious and political institutions. They had just read an article by Haldun Gülalp explaining that secularism in the new Turkish Republic required both the privatization of faith (taking religion out of the public–and political–sphere) and, ironically, the control of the state over all religious institutions. The mufti spoke briefly, then answered questions. Some seemed strangely irrelevant, while others began to clear up our confusions. The mufti is employed by the government; he administers institutions that train those who do the call to prayer and the schools that train the jurists and control religious education in public schools.

We had to leave quickly to go to Yildiz University (our third campus tour) to talk with Professor Gulalp. The students asked him their questions about his article, about the relationship between the state and religion, and about his own answer to the morning’s question. Why is Turkey so unstable? He disagreed with all of their opinions, focusing instead on explaining how the military justifies their interventions (Rousseau’s notion of the difference between the popular will and the popular sentiment.) Once again, I was impressed with the students’ insights, and their clarity in both asking and responding to questions. Many carried the discussion into their own blogs (click links on the right).

Experiential Learning

This was the educational philosophy we advocated when I headed UNC’s first year seminar program–that students learn better when through experience and discovery. This week, from Monday’s walking the Byzantine land walls to Friday’s site visit to a hamam, I learned that “experiential learning” really is effective–and, sometimes, a bit awkward.

And exhausting. I’m quite behind in the blog posting because the end of each day has come very late this week, because there is always tomorrow to prepare, because I’m experiencing so much I haven’t time to write about it. The students’ blogs seem a few days behind, too.

Before the week even began, we were scrambling to make the schedule work. Monday’s weather looked like it would be fine and cool, perfect to walk the land walls from the Sea of Marmara to the Golden Horn. David made this map. During the Byzantine period, the entire city was surrounded by walls. Many are crumbling now; some are in the process of being restored.

We began at Yedikule, the seven tower structure the Turkish government turned into a park. The views from the top were spectacular, though, an acrophobe since childhood, I only climbed one tower. The students quickly learned that I was very nervous with their energetic wall-scaling. They delighted in seeing me anxiously cover my eyes, and seemed to become more and more outrageous to get the response. They are all adults, I kept reminding myself.

The walls go through fascinating areas of the city, cutting through sections tourists don’t see. We wondered why so few tourists walked the walls, and how people who lived along these millenium-old structures perceived them. Many of the neighborhoods we walked through were quite run-down, the people very poor. Some of the unused archways seemed to house the homeless. At the same time, the government seems to be investing large sums in restoring sections of the walls. What do the walls mean? How do the Turks view them? What is it like living in a place with so much history?

All back down safely!

All back down safely!

The week seems a blur now. There is so much to see and to do, that we planned things for mornings, afternoons, and evenings. Tuesday we visited an NGO that focuses on women and Islam, and listened to a wise woman answer many questions. I’ve been struck for years that Cemalnur’s answers only seem to make sense some time later. Instead of simple answers about religion and the state, what the NGO does, how sufis are different from other Muslims, she tells stories and suggests parallels. When we returned to Europe, two of the students did the first site project: Sirkeci (the 19th century train station) and the Orient Express it hosted. They spoke of the way the railroad tied Istanbul with western Europe, of the elites that frequented it and the culture they fostered, of the effects of railroads on the Ottoman (and later Turkish) state.

Then most of us went to Tumata to hear Tatar and Uyghur folk music played on remarkable instruments in a musical museum. Like last week, the music gradually became more devotional and the audience more participatory, various students began to figure out how to play the drums that the regulars handed them, and one of the regulars began to turn–the sema.

As we prepared to leave, they insisted we stay for soup, then for dinner, then for the celebration of the birthday of one of the musicians. When I returned upstairs after helping put away dishes, I found all the UNC students up and dancing with the musicians.

Wednesday was museum day, Dolmabahce in the morning, and the Military Museum in the afternoon. Two students took us through the Military Museum, emphasizing how the choices and content of the exhibits reflected the way the Turkish directors wanted their history to be understood. Thursday we visited Bogazici University, where Sevket Pamuk did a remarkable presentation on changes in the Turkish economy over the past century–and hosted us for lunch! The students returned in time for Turkish class. They can put verbs in their sentences now.

Friday morning we sat in the courtyard of the “Blue Mosque” and heard stories about the man who built it, about his life and the issues surrounding his accession to the Ottoman throne, about his goals for the structure and the reason he placed it where he did. Then Gunhan, an Ottoman historian who doubled as a tour guide, took us inside, talked about the tiles and the structures, the arches and the domes. Over lunch, we talked about history writing and national identity, about the challenges of being a historian. Then he took us to neighboring Aya Sofya and did the same thing! We learned about the Emperor who build it, the reasons he needed such a monumental structure, the design and the redesign, the mathematicians who worked out a way to keep such a massive dome from falling. And I learned that it is just as striking to walk into Aya Sofya regardless of how many times one has seen it before. Gunhan was amazing, wearing his tour guide license along with his historian hat. Again I was struck that the “gee whiz” of tourism is a delightful but limited phenomenon. History matters, even (especially?) in the face of spectacular structures.

Two of the students had decided that they would do their site presentation on hamams. After telling us about the origins, economy, and social functions of public baths, we actually did one. Gedikpaşa built his hamam in 1475, making it one of Istanbul’s oldest. It’s a bit rundown at this point, and hasn’t been restored to tourist/spa quality, which is one of the reasons the students wanted us to go there. Countless groups of women have used it over the centuries to wash–and to recreate community. It was amusing to watch that happen, as the UNC women began to splash water around and sing. Needless to say, I’ve no idea how much splashing went on on the men’s side.

Cross-Cultural Amusements

Aylin, one of Katie’s friends, invited us to come to Sabanci University to meet her students. I’ve never gotten bored with crossing the Bosphorus, and it seems the students share my enthusiasm (even at 8 a.m.) After a long bus ride, we were ushered into a darkened classroom with some 20 Turkish university students. A few minutes of sitting at their own table convinced the UNC students to take action: they suggested integrating the room.

Even sharing the same tables led nowhere. The Sabanci students had prepared fascinating PowerPoint presentations for us. Aylin had left them free to choose the topics we would need to know about Turkish culture. I was surprised by some: folk dance (do they do this?), amused by others.

I had misunderstood the process, and we hadn’t prepared anything in response. Kelly showed remarkable poise and creativity in finding photos online to describe “our” culture as we shouted suggestions: UNC’s high points (the Old Well, the Dean Dome and football stadium, Michael Jordan playing in Carolina Blue), a map, a tarheel emblem, “our” food (sweet tea and biscuits, OK, but pork barbeque Kelly?) It was Edward who really broke down the cultural barrier when he decided to show them the soulja boy dance.

After an enthusiastic round of applause, the room became quite noisy as the two groups talked, laughed, and exchanged contact information. They took the UNC students on a campus tour–a bit nervous about showing off their athletic facility after seeing the photos of ours.

Turkish/Art

I’ve often wondered how people teach art. The Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts is overwhelming. They have objects dating back before the building of Bagdad, and the collection is spectacular. I wander from carpet to pot to door to map to miniature, gawking at beautiful colors and complex shapes. I was fascinated watching the others. Some stayed close by Nazende, an art historian from Marmara University, who talked about symbols and techniques. (Muslims are much more symbolic in their art: God is often represented by a tulip, Muhammad by a rose, Ali by a carnation… Iznik potters don’t get the red really right until the sixteenth century…) Others wandered apparently aimlessly, while still others walked through the whole exhibit and sought an exit, air, and less visual stimulation.

We all gradually made our way out onto the terrace, to see a remarkable juxtaposition of famous (fabulous) monuments.

Then we asked Nazende questions. In European art museums, the focus is on paintings. Why are all the objects here useful items instead? We heard about reforming Ottoman elites’ efforts to introduce painting, efforts that were quite unsuccessful. We talked about calligraphy as art, the importance of words in this artistic culture, thinking about Efdal’s demonstration. We talked about values and arts and monuments–is this teaching art?

And then the students had their first formal Turkish lesson. They have obviously been testing out their growing vocabularies as they acquire new phrases, and had been requesting classes since their second day in Istanbul. They were picking things up rapidly, living on the local economy where most people selling to their price range speak no foreign languages. Yekta had done a terrific job as teacher and translator, but they were pushing for more, strongly motivated, it seemed, to be able to really communicate with the Turks they were meeting. Their blogs reflected that strong impulse, so I found a teacher, with Katie’s help. Hande teaches English to adults all day long, but agreed to take on another group. This was the most light-hearted language class I have ever watched.