Posts filed under ‘Architecture’

Ankara

The bus to Ankara turned out to be a bit more exciting than we had planned. The driver claimed he didn’t know he had to stop in Ankara on his way to Istanbul, so insisted on passing the exits. After a series of phone calls, and some remarkably polite and persistent intervention from Yekta, we arrived somewhere–anywhere–in Ankara and got off the bus. We managed to find four taxis despite the late hour (1:30 am) and made our way to the dorms at Bilkent University.

When our planned speaker postponed the next morning, I offered the students a day off to explore Ankara. Instead, they wanted to go out to Gordion, a site where UNC Classics Professor Ken Sams leads an excavation. After taxi, dolmus, and bus rides, we found ourselves looking up at a mound that had previously been a city.

I loved Ken Sams’ discussion. We had encountered many guides who provided details about the stones. Ken is a historian. He told us what is known about the people who had lived at Gordion, how we know the things we know about them, and what we don’t know yet. As we stood looking into the stone walls between structures, he told us that the same things had been found in each. These implements provided information on food and textile manufacturing technology, but not why the same things had been found in each room. Archaeologist still don’t know who did the production, and how labor was organized.

I loved Ken Sams’ discussion. We had encountered many guides who provided details about the stones. Ken is a historian. He told us what is known about the people who had lived at Gordion, how we know the things we know about them, and what we don’t know yet. As we stood looking into the stone walls between structures, he told us that the same things had been found in each. These implements provided information on food and textile manufacturing technology, but not why the same things had been found in each room. Archaeologist still don’t know who did the production, and how labor was organized.

Ken explain to us the kinds of things archaeologists can know, what they wish they knew, why they think other kinds of records may no longer exist. And we learned that archaeologists sometimes revise their previous judgements. We visited the tomb of King Midas. Ken explained, though, that new dating suggested that the corpse was Midas’ father, making it still the tomb that Midas built, but not quite, well, the tomb in which he was buried.

Ken explain to us the kinds of things archaeologists can know, what they wish they knew, why they think other kinds of records may no longer exist. And we learned that archaeologists sometimes revise their previous judgements. We visited the tomb of King Midas. Ken explained, though, that new dating suggested that the corpse was Midas’ father, making it still the tomb that Midas built, but not quite, well, the tomb in which he was buried.

- Into the Tomb

At the small museum next to the excavation, one of the graduate students working at the site explained that the local population had emulated Hellenistic pottery–it was quite the style in some circles. But they didn’t understand some of the Greek pottery’s particular functions, so their imitations are of great interest when analyzing cultural transmission. Ken had talked about the Greeks’ bringing their own languages and customs to Gordion–and to Anatolia generally–but both he and his student emphasized that the local, pre-Greek population remained present throughout the countryside. So what is a “Turk?” It was Phrygians who lived at Gordion–or anyway, it was a Phrygian government who ruled the people. And, it seems, the local population learned from the Greeks, but the Greeks also picked up some of the local customs.

The second Ankara morning was devoted to Atatürk, of course. I got to stay at the dorms with an ill student while William took the students to Anıtkabir, Atatürk’s mausoleum and museum. Their guide was a friend’s father, a retired politician, former cultural minister, and a great admirer of the Founder. After reading of, talking about, and observing the Atatürk cult from afar, the students were able to get right to its center. I am sorry I missed it, but was delighted to hear about what the experience was like for them. (Check out their blogs, links on the right.)

By afternoon, everyone seemed well enough to go to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, where Thomas Zimmermann, archaeologist from Bilkent, talked to us about Turkey’s pre-history. He began outside, talking about the buildings themselves, how the project of taking Ottoman hans and turning them into an archaeological museum was an inherently political project. The goal was to claim a distinctly Turkish past, a past that predated the Ottomans, the Seljuks, and even the Byzantines. It reminded me of the new Lebanese state’s efforts to find its Phoenician past, and the nationalist Egyptians’ attempts to claim Pharonic origin. In this case, the new Turkish nationalists used archaeology to trace a very long historical trajectory, claiming that they descended from the Hattas and the Hittites.

This is an award-winning museum, displayed well and labeled clearly, organized coherently and quite beautifully presented. It creates a linear historical path from pre-historical people to the Turkish present, almost ignoring the Greeks and Romans, who seem to be off limits– invaders instead of true inhabitants of the heartland. I found myself wondering how historians get to choose which groups are authentic and which are outsiders. But in any case, I think the students understand that there is much at stake in the project, more important than memorizing which artifacts go in which era.

Thomas’ fascination with metals was clear–it’s always exciting to have a teacher who is enthusiastic about his work.

Dr. Seuss’ Inspiration?

After a difficult farewell, we returned to Konya in time to meet the Fez bus for the trip to Cappadocia. On the way, they stopped at a remarkably intact Seljuk-era caravanseray. The spiral dome impressed us all.

So did the fascinating collection of heads, another in an astounding collection of Turkish public sculpture we have seen during our travels. Atatürk, of course, is in the center. Those behind him include an enlightening and eclectic collection of Turkish heros: Ottoman Sultans Mehmet the Conqueror and Sulayman the Magnificent, legendary Turkic hero Dede Korkut, mythic Turkic tribal leader Oǧuz Kaǧan, Seljuk Sultan Alparslan, famed architect Sinan, Turkish poet and MP Mehmet Akif Ersoy, and Ibn Sina (Avicenna), medieval scientist and philosopher.

In a few hours, we reached Uchisar, a small town in Cappadocia frequented by French and Italian tourists. The landscape is astonishing, carved by wind and water from the volcanic stone. Over the centuries, humans have helped with the carving, digging homes and public buildings into the rocks. The students insisted on staying in Kilim Pensiyon’s cave rooms.

- View from the Terrace

Landscape by Dr. Seuss?

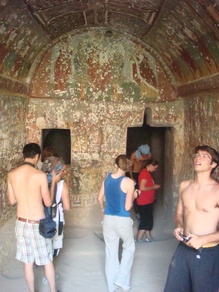

For two days, we climbed over rocks and explored inside caves, walked along streams and admired the Byzantine churches that still exist around the area. We got to the point that we could actually identify most of the images in the cave churches, images most of us had seen for the first time in Istanbul.

Iconoclast Version

But the walking was intermittently difficult, and the climbing a bit intimidating. After a difficult swim in a reedy, mud-bottomed lake formed inside a volcanic crater, I wondered whether this trip had somehow morphed into outward bound. I sat out the walk along the Ihlara valley, where William and the students explored more caves and admired more churches. I did get to listen in on the conversation in a village restaurant as the owner tried to convince two bureaucrats that they really did need cable and internet -–I was exhibit A, with my laptop and nothing to connect to. (They also wanted to be able to run credit cards, and needed a cable for that. Three months, they were promised.)

- Outward Bound?

Everyone was a bit tired as we waited to be picked up by the Fez bus for the trip to Ankara that evening. Two weeks on the road is a long time.

A Four Mosque, Two Museum Day

We met the Fez bus for the ride to Konya. Their staff and the driver agreed to a short stop at the Seljuk mosque in Beyşehir on the way. I got to take the microphone and explain to the students–and the others–why the mosque was important. Eşrefoglu mosque is one of the oldest standing wooden mosques, built around 1229. It also functioned as an observatory, the water in the central courtyard was open to the sky, allowing people to watch the movement of the stars and the moon. Astronomy was important for medieval Muslims, initially to indicate days and times of prayer, but eventually simply as scientific exploration. The mosque’s wooden columns and capitals are beautiful, and the tile is that Seljuk blue so different from the blue of the Blue Mosque and other Ottoman monuments.

We arrived in Konya, called our friend Mehmet (owner of a carpet shop, Ipek Yolu), and he brought his pick-up truck to carry our luggage while the students walked to his shop. After we checked in to the hotel around the corner and had lunch, Mehmet drove us around Konya. He not only sells carpets, but has also worked to reintroduce natural dyes to the local producers. First stop was to the home of one of his weavers, a very experienced woman who has been making kilims for him for decades. Pay is $80/square meter, which provides a significant supplement to the family’s income. We saw her weaving a Navajo kilim–another of Mehmet’s new projects. As those of us who have traveled in the American southwest can attest, Navajo blankets and rugs have gotten quite expensive. Mehmet’s weavers are now producing traditional southwestern patterns for sale in Santa Fe.

Next stop was his own dying shop, where he explained the process by which he has tried to match the colors of antique carpets using plant material. The vats are in a large garage, the dyed wool skeins hanging out to dry in the yard. He showed us a terrific old carpet that desperately needs restoring. He unweaves very old undyed kilims to match the old wool, then dyes them to match the color of the antique carpet. An experienced rug knotter will take his wool and restore the antique.

The students were fascinated with the details of weaving, dying and restoring, but some appreciated even more the drive around Konya’s residential neighborhoods. They noticed that very poor households were located in the same neighborhoods as more affluent families, and they enjoyed chatting with the children and petting the cats.

Our second day was the mosque/museum day. Mehmet’s younger brother Muammer was our guide, as we began a day of the kind of intensive high-cultural tourism we hadn’t done since we left Istanbul. I found myself wondering again what the goal of this kind of day is. Is it just exposure to new kinds of things? Some kind of mosque-appreciation project? Museums can be either hours of discovery or bored slow-paced strolling from cabinet to display to statue.

First, it was a 17th century mosque, like a classical Sinan-style mosque updated to baroque. They made the comparisons, got the differences. Then we went to the tomb and attached mosque of Şemsi Tebrizi. There is some dispute about whether Rumi’s teacher is really buried here, and the circumstances surrounding his death. What is certain, though, is that many people see this as a very holy space. The students were impressed with the intensity of feeling displayed by at least one of the visitors–an intensity that Muammer insisted would not have been approved by Rumi himself.

Our third mosque of the day was the central mosque of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, Alaeddin mosque. It is an odd structure, expanded over time as more and more people had to fit inside. The blue-tiled mihrab is striking, as is the intricately carved minber. Most striking is probably the forest of columns and the apparent lack of planning for the whole structure.

Museum one of the day was full of Seljuk-era wood and stone carving. I knew that Konya was an important city on the old silk road. Nonetheless, I was surprised to see the carvings of lions and elephants, and even more astonished with the Seljuk carving of the Buddha.

How would the Seljuks have know to carve elephants? I tried to take the opportunity to reiterate the importance of this region for international trade. We left the museum and hurried many blocks to the tile museum, but it was closed for lunch, so we decided to do the same.

After lunch was the big event of the day. Mehmet had arranged for a local historian to take us to the Mevlana “museum.” Mevlana is the name by which Turks know the best-selling poet in America, the man we call Rumi. The government of the young Turkish Republic outlawed sufi orders, worried that they might become alternative bases of authority. They have turned Mevlana’s tomb, a site of pilgrimage and devotion, into a museum, but a museum in which half of the people are engrossed in prayer and half file through with little understanding of what the building is about.

William and I had been there before, and were struck once again by the intense religious environment that the government was unable to displace when it turned the site into a museum. The mosque/museum tourism day seemed to rise to a whole new level of ambiguity at Rumi’s tomb–the line between the two genres erased more dramatically than it had been even at Hagia Sophia. The tekke in which new members of the order had studied now contains displays of the ways the young students lived, and the devotional turning ceremony has become folkloric dance. The crowds of visiting Turks were here to make a pilgrimage; the crowds of foreign tourists looked quite silly wearing leapord-spotted wraps to cover their shorts-clad legs. It was an odd combination.

Our guide, the local history teacher, seemed, like everyone else in Konya, to have his own narrative about and relationship to Mevlana (Rumi). He claimed that Şems was not Mevlana’s teacher–apparently, it seemed important to him that Rumi come up with his own ideas without anyone else’s help. Muammer was convinced that Rumi was a rational man who emphasized rational discourse and thought and would have profoundly disapproved of the kind of emotional intensity we had seen in the morning. For the religious, he is a spiritual leader and a lover of God. For the secular, he is a notable reformer. For the outsider, he is the teacher who insisted on including all. The “museum” experience of reading and listening to the significance of each object and the way the building was created seemed to detract from the human experience of just simply noticing the feelings of the place and the way people responded to it.

One more mosque on leaving Mevlana: a 19th century structure with large windows and ornate minarets, a mosque that seemed to emulate Dolmabahçe’s style. Very modern, European. Enough mosques! We had seen an impressive range of dates and styles over the course of the day.

We got cleaned up and went to a “traditional” restaurant serving local foods. We ate sitting on the floor around round trays, having no idea that this was to be good preparation for our next journey, to the village.

(Can’t resist another in the continuing McPhotos series)

Church to Mosque

After last week, I thought we needed to take things a bit slower. Monday had not been a promising start–we grappled with questions of Turkey, religion, and politics from 10 am until dinner was over nearly 11 hours later.

Tuesday we got to enjoy the final student site presentations. The morning was at Kariye museum, a strangely asymmetrical domed structure with the most remarkable and spectacular mosaics still intact. William and I had gone to the old Byzantine church-turned mosque-turned museum some years ago with our kids and our friend Bob Ousterhout, who had written his dissertation on the structure. He is one of the most remarkable teachers I have ever met, and his explanations have stayed with me.

Tuesday we got to enjoy the final student site presentations. The morning was at Kariye museum, a strangely asymmetrical domed structure with the most remarkable and spectacular mosaics still intact. William and I had gone to the old Byzantine church-turned mosque-turned museum some years ago with our kids and our friend Bob Ousterhout, who had written his dissertation on the structure. He is one of the most remarkable teachers I have ever met, and his explanations have stayed with me.

Then it was Kalenderhane, another Byzantine church recreated as a mosque. Both student pairs described the transition, and Zoe actually distributed a page with the basic mosque structures that the students colored while she described the basic needs for the conversion.

All day Wednesday we had conferences to talk about oral history and final projects, and Thursday provided everyone with some work time. Thursday evening was party time! Robin, the wonderful landlord, brought the Efes and some Turkish food, the students provided soft drinks, fruits and vegetables. William grilled, and the Burch students met a group of visiting music students and a number of Robin’s friends. The view, both on and off the terrace, was terrific.

Turkish/Art

I’ve often wondered how people teach art. The Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts is overwhelming. They have objects dating back before the building of Bagdad, and the collection is spectacular. I wander from carpet to pot to door to map to miniature, gawking at beautiful colors and complex shapes. I was fascinated watching the others. Some stayed close by Nazende, an art historian from Marmara University, who talked about symbols and techniques. (Muslims are much more symbolic in their art: God is often represented by a tulip, Muhammad by a rose, Ali by a carnation… Iznik potters don’t get the red really right until the sixteenth century…) Others wandered apparently aimlessly, while still others walked through the whole exhibit and sought an exit, air, and less visual stimulation.

We all gradually made our way out onto the terrace, to see a remarkable juxtaposition of famous (fabulous) monuments.

Then we asked Nazende questions. In European art museums, the focus is on paintings. Why are all the objects here useful items instead? We heard about reforming Ottoman elites’ efforts to introduce painting, efforts that were quite unsuccessful. We talked about calligraphy as art, the importance of words in this artistic culture, thinking about Efdal’s demonstration. We talked about values and arts and monuments–is this teaching art?

And then the students had their first formal Turkish lesson. They have obviously been testing out their growing vocabularies as they acquire new phrases, and had been requesting classes since their second day in Istanbul. They were picking things up rapidly, living on the local economy where most people selling to their price range speak no foreign languages. Yekta had done a terrific job as teacher and translator, but they were pushing for more, strongly motivated, it seemed, to be able to really communicate with the Turks they were meeting. Their blogs reflected that strong impulse, so I found a teacher, with Katie’s help. Hande teaches English to adults all day long, but agreed to take on another group. This was the most light-hearted language class I have ever watched.